Editor’s Note: When this blog was started by a group of friends, we hoped it would become a running dialogue of our interests. In the purest sense, we would be communicating with each other, while letting others in on the conversation. Admittedly, there has been little communication between the contributors, with some spending more time in Bobcat Territory than others. This Blogcat is my attempt to get back into Bobcat Territory and insert myself solidly into that running dialogue. What better way to do so than to respond directly to our most recent Blogcat!

_____________________________________________

Yesterday, one of our esteemed Bobcat Territory contributors, Josh Kambour, posted a Blogcat detailing what he believes to be the inherent problem with March Madness. I’ve got to disagree.

A quote from the well written essay: “One of the reasons our society loves watching sports in the first place is to watch the best in the business go at it – because these athletes represent the pinnacle of the competition.” It’s true that good talent in the game makes the play more enjoyable for spectating. I mean, no one wants to watch a youth soccer game where the players chase the ball like a swarm of flying insects when they can otherwise view Spain and Argentina meeting for ninety minutes of the beautiful game. Perhaps even a little extra time if we’re so lucky. However, I argue that the pinnacle of the competition in college basketball, and other team sports, is not met through individual talents but rather collective perseverance.

Kambour mentions the appeal of the Cinderella Story and the excitement of a David over Goliath moment, but I think he overlooks what many consider the true spirit of competition. We compete to see who or what is better, and in team sports this means determining which collection of players is better at the given game/sport for the allotted period of time. We often hear losing athletes and coaches quoted after contests saying things like, “we just got outplayed,” or “the better team won today.” These cliches may just be fodder for the press, an attempt to get the mic out of your face when all you really want to do is move past the loss or sulk at your locker all lonesome-like. There is also truth behind these lines. They are a confession of sorts. A realization that “Hey, I guess we aren’t as good a team as we thought we were.”

If the pinnacle of the competition was represented simply by the “best” going at it, then there would be no need for March Madness, postseasons, qualifying rounds or any sort of tournament for that matter. We could just take the two highest ranked teams in their given sport and have them match up for a one time championship game. This may be a scenario The Kid is perfectly fine with, but it is one I cannot stomach. Preseason rankings are hardly ever an accurate gauge of what will come, and postseason seeding can sometimes be misleading as well. Sometimes the better team on paper isn’t actually the best team.

Take the current, and soon to be extinct, college football national championship. It is determined every year when the #1 ranked team plays against the #2 ranked team in the country. The best of the best of the best. Yet it is wrought with controversy and divisive commentary every year when three, four, sometimes even five teams seem deserving of a shot at the title. What makes them deserving? It’s the possibility that for those 60-minutes, those 4-quarters, on any given Saturday an ostensibly worse team could play a little harder, want it a little more, make one less mistake or one more spectacular play that proves they were the better team that day when it really counted.

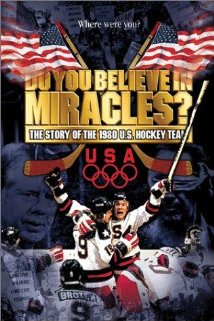

One of America’s most heralded sports stories is the Miracle on Ice. Yes, this is considered a Cinderella story, but in reality is that what makes it great? I say no. We are told a ragtag group of college hockey players beat the big bad military-style Russian national team in a game with Cold War implications much grander than pure sport. Our American team, however, was not ragtag. It was comprised of the very best collegiate players at the time who were hand-picked, after grueling tryouts, by the best collegiate coach at the time.  It would be like Coach-K holding open tryouts and picking the best college players for the Olympic basketball team. In essence, they were the best of the best. What makes the game great, though, is that many of these players were bitter rivals when donning their respective college uniforms. In order to win in the Olympics they needed to play cohesively as a unit. Coach Herb Brooks’ most daunting task wasn’t beating the Russians. It was getting his players to play as a team, to compete as a team. That’s the pinnacle of competition.

It would be like Coach-K holding open tryouts and picking the best college players for the Olympic basketball team. In essence, they were the best of the best. What makes the game great, though, is that many of these players were bitter rivals when donning their respective college uniforms. In order to win in the Olympics they needed to play cohesively as a unit. Coach Herb Brooks’ most daunting task wasn’t beating the Russians. It was getting his players to play as a team, to compete as a team. That’s the pinnacle of competition.

So, if Providence and Colorado meet in the Final Four there’s no reason to question whether or not that same game would’ve been appealing in December. It’s not as though they entered a cheat code to get there. They played the “better” teams on the same court, with the same ball, the same rules, and they won. They out-competed them. If those talented, high-profile teams were truly the better teams then they would’ve been the better teams.

I love the rebuttal! Now, time for throwbacks.

I certainly recognize that the opinion I offered forth would be fairly unpopular. In fact, Bullets – a fellow loather of college basketball – and I have learned over time that we should actually just shut up and smile along, rather than voicing our distaste of the sport, since so many people vehemently disagree with our stance. The same goes for my take on March Madness itself. When I’ve hinted at my feelings at work, people just look at me flabbergasted that I have such heretical views.

I agree with Ezra’s post, while also feel like it’s not exactly disagreeing with my comments from yesterday. I hadn’t been arguing that the more talented teams always deserved to be in the final. Of course, if they lose, then they lose, and as long as the system is fair – that it favors no team, and the outcome is based on performance, rather than opinion – then so be it. The BCS, as was mentioned above, doesn’t seem fair, because preseason rankings, and people’s preconceived notions that certain conferences (i.e. the SEC) are better, often influence who gets to go to the big dance. In a sports utopia, those reputations wouldn’t affect who gets to wear the championship belt.

However, I still believe in my previously stated stance. Ezra cited a number of sports cliches in support of his viewpoint (e.g. they were the better team that day). Here’s another sports cliche: “when we play like that, nobody can beat us.” While that probably gets uttered in cases when it doesn’t actually apply, there are certainly situations when it does seem to be the case. The problem is, as Ezra has pointed out, we, as human beings, perform inconsistently, and thus that level of play is not always reached. That is something cool about sports. That a team who’s level of performance ranges from D-B+ can, on its good day, beat a more talented team whose performance ranges from B-A+. I imagine one could bring up a point that, well as long as you won you played well enough, but that doesn’t mean you were scratching the pinnacle of the sport.

When those less talented teams do win, that lowers the ceiling on the potential. Not necessarily the level of drama, I will admit, but theoretically the level of skill, for sure. And this is why, while reputation has no place in determining who’s deserving of winning, it certainly has a place in determining how excited I will be to watch something.

I’m a bit all over the place, but let’s consider the old yarn of the tortoise and the hare. Certainly the hare deserves to lose. He didn’t play well, the tortoise played better, and that’s that. Does that mean that we’re overjoyed with that upset? I personally would have rather seen the hare reach its full potential and kick ass. Then, in the next heat, it’ll be a much closer race against the deer, rather than seeing the tortoise get his ass kicked.

Also, let’s imagine that I was drafted into a four-man, single elimination HORSE tournament against Larry Bird, Kevin Durant, and Stephen Curry. The first round consisted of one letter, and then the finals would be the full word. I go up against Durant in the first round, and I’m a massive underdog, but because of the small sample size, I luckily hit my first shot, KD’s shot rims out, and I move on to the final.

Now, you’re sitting at home, and instead of seeing KD go up against Bird/Curry, you get to see me. How pumped are you? Are you saying, “huh, I guess ‘the better team on paper isn’t actually the best team”? No. You’re pissed because that would have been an EPIC FUCKING GAME OF HORSE. And the small sample size ruined it.