I noticed an interesting trend when looking at the list of nominations for Best Picture at the upcoming 93rd Academy Awards. Judas and the Black Messiah tells the story of the murder of Fred Hampton and the Black Panther movement of the 1960s through the lens of a crime thriller. Mank tries to recontextualize the narrative behind one of the most famous important movies in American cinematic history. Trail of the Chicago 7 is about anti-Vietnam protesters and the history of American liberalism, as told from the unbearably smug perspective of Aaron Sorkin. Nomadland is about the Great Recession, Minari is set in the 1980s and tackles America’s history of prejudice against Asian-Americans, and even Promising Young Woman has been cast as a specific allegory for the #MeToo movement.

Depending on how you frame it, 6 of the 8 total Best Picture nominees are, in some way, about history. More specifically, they are about how we in the present reconcile our shared cultural history. A movie like Judas and the Black Messiah opens up an old wound that many people not old enough to remember the 1960s didn’t realize even existed; it forces a predominantly white audience to directly confront the inconsistencies in our narrative of how the Civil Rights movement unfolded. It tries to make palatable a radical political narrative by using the comfortable frameworks of genre convention (both as a standard Hollywood “biopic” and as a crime thriller).

And now I am going to hard pivot from talking about movies most of you have seen or at least heard of to talking about movies most of you have never seen nor heard of. I just pulled the same trick as Judas, I am trying to make palatable a deep discussion of esoteric European arthouse cinema by contextualizing the themes I want to discuss in more familiar terms.

Béla Tarr (Hungary) and Theo Angelopoulos (Greece) are anything but household names. While some of Tarr’s movies sometimes make their way onto streaming services (The Turin Horse was on Amazon Prime for a while, Sátántangó was recently put onto the Criterion Channel), Angelopoulos’ works only seem to circulate as rips from long out-of-print Region 2 DVD sets. Every once in a while an arthouse cinema or film school will host a screening. But generally there isn’t much exposure to their works, outside of the kind of people who go out of their way to do deep dives into the European film scene.

Which is a damned shame! Both are interesting and idiosyncratic filmmakers. None of their works would ever be likely to be as commercially appealing as a movie like Judas and the Black Messiah, but for fans of film as an art form they have a lot to offer. There are a lot of aspects of their careers that I would be interested in discussing, but for now I am only going to focus on the way they deal with this idea of reconciling history.

I’m going to focus on Tarr’s masterpiece Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) and Angelopoulos’ only-movie-of-his-I’ve-seen The Hunters (1977). There are a lot of interesting parallels between the two, especially in that the narrative and thematic core of each revolves around a corpse. In the case of Werckmeister Harmonies, the corpse is that of a whale prominently exhibited in the center of town, while in The Hunters the corpse is that of a dead partisan from the Greek Civil War whose body is still mysteriously bleeding almost 30 years after his death. Since few of you will have seen either, I will try to keep the discussion driven by screenshots of specific scenes.

(For all of the embedded screenshots, you can click them to open a larger version of the image to look at. I apologize that the quality isn’t the best, these are screenshots from VLC media player. Also seems fair to give you the NSFW warning that there is a fully exposed naked old man in one of the screenshots.)

A natural place to start would be, for each movie, the introduction of the corpse. For The Hunters, this is also literally the first scene of the movie. It opens on a wide shot of a bleak winter landscape, in which the titular hunters (who, we later learn, are bourgeois vacationers) can be seen trudging through the snow.

The hunters are dwarfed by the scenery around them. You can’t make out their features or really even tell them apart. They are just vaguely human-shaped blobs situated within the mountains of Greece. They walk slowly towards the camera, with no sound except that the harsh whistle of the wind.

It takes about one minute of screen-time for the hunters to get close enough to begin to notice any distinguishing features. One minute may not sound like much, but consider that the average shot length in modern mainstream movies like The Avengers (2012) is only 3.16 seconds. Meaning, that while these hunters were walking slowly and speechlessly forward you could have seen almost 20 different shots of Chris Hemsworth destroying alien robots … and this shot isn’t even over with!

Anyway, after that minute, we hear an exclamation of alarm from off-screen, and the camera pans (no cuts!) over to the right to follow another hunter running hurriedly towards the rest of the group.

The hunters huddle in deliberation, though we cannot hear their voices over the wind. After a moment, the runner leads them back from the direction he came from, and the camera follows the group as they follow. Though now we can see several of the characters in detail, we still see them only from a wide angle (they are still subordinate to the landscape in the frame). There is no focus on any one individual hunter or what they are feeling in that particular moment, just a generalized sensation of group anxiety/panic.

Finally, emerging from the right-hand side of the frame, we see the source of the alarm. There is a dead body lying in the blood-stained snow. The hunters approach and stare at the body in silent disbelief.

One of them mutters the first dialogue of the movie, saying only “This story had ended in 1949. What the hell? I don’t understand…” After he trails off, the hunters look uncertainly around at the surrounding mountains. The scene ends as the action of the movie shifts forward in time to the hunters bringing the body back to their hunting lodge.

All told, this opening scene is 2:54 minutes long (i.e. a little more than 55 Thor-punches). This dedication to long, slow-developing shots is a feature of both Angelopoulos and Tarr. The average shot length in The Hunters is approximately 3 minutes, while the average shot length in Werckmeister Harmonies is closer to 4 minutes. While both directors conduct these long takes with complex, balletic staging of the actors and camera movements, the way in which they use these tools enforces very different themes.

Fully unpacking the scene described above requires knowing some historical context about Greece, the sort of context that would only be obvious to a Greek audience at the time of the movie’s release in 1977. The body that the hunters find is that of a communist partisan from the Greek Civil War of 1946-1949. That war ended (aided by assistance from the United States) with the bloody defeat of the communist guerillas and the establishment of a weak pro-capitalist government that would eventually become a military dictatorship. As is slowly revealed over the course of The Hunters, the characters that discovered the body are all individuals who in one way or another directly profited from the Civil War (e.g. some were former communists who betrayed their former comrades for clemency and status, others were wealthy politicians who funded bloody reprisals against communist sympathizers, etc.).

The opening shot perfectly encapsulates the way the movie deals with these characters and these ideas. There is no focus on any one character or any attempt at revealing any character’s emotional state. They are just small blots within a hostile environment. The only notion of a reaction is a generalized group fear and unsettlement. The only dialogue is a brief statement confirming the historical context and the surprise at the hunters of being confronted with a dark moment of their shared history.

That is, the characters aren’t meant to be viewed as real, individual people, but as more or less blank slates representing a broader slice of Greek society. The movie isn’t about individual people, it is about the way society as a whole deals with its own history. Here, it is with fear and aversion. They don’t want to confront the ugliness of their past since it reveals the brittleness in the foundations of the present.

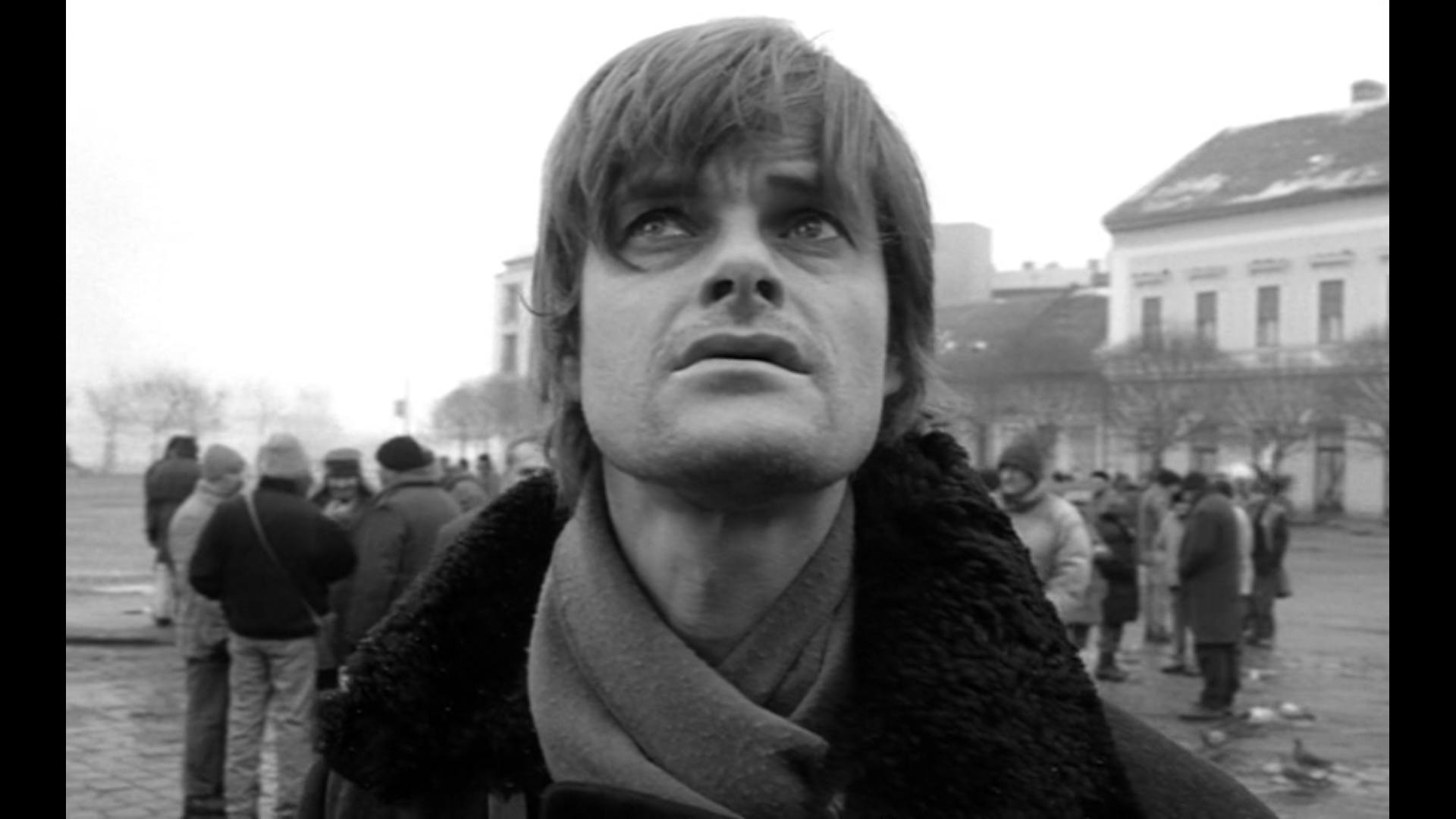

In Werckmeister Harmonies, we don’t see the carcass of the whale until about 40 minutes in. Like Angelopoulos, Tarr begins the scene with a wide shot of a cold and dreary looking place. This time, though, it not the harsh Greek wilderness but a stark town square populated by a faceless shivering mob and the mysterious truck (whose arrival is depicted in a previous scene).

From the right side of the frame emerges Valuska, the central character of the movie. The camera follows him as he walks forward towards the truck. He remains the pre-eminent figure in the frame for the duration, emphasizing that it is his presence in the frame we are to attend to (and his reaction to the surroundings that is paramount).

As the camera follows him, it slowly dollies around to show him in profile, and we catch the fear and confusion in his expression as he scans the square.

At first, though, Valuska is not interested in the crowd. Just the truck. He strides purposefully for it and examines it closely, trying to imagine what mystery it contains. The camera continues to circle him, showing us in one fluid movement what he is attending to and how he is reacting.

The only movement in the square (and, indeed, the only sound we can hear besides Valuska’s footsteps scraping the wet cobblestone) is from a flock of pigeons; the flocks of people stand stoic and still.

Unable to glean anything from the truck, Valuska turns his scrutiny towards the crowd. He begins to walk through it, examining the people he passes. For the next two minutes, the camera follows him. Even when he moves to the back of the frame, his expression is still the focus.

The combination of his movement and that of the camera tightly framed around him is disorienting. It confuses the geography of the square so that it is difficult to determine exactly where he is in relation to the truck or any other landmark. That is, in contrast to The Hunters depicting its characters as being anonymous features within a landscape, Werckmeister Harmonies is allowing the landscape to revolve around Valuska. The landscape is only the backdrop against which we are to perceive his emotions.

Finally, a new sound is heard from off-screen. The sound of a motor. Valuska turns towards the sound, and the camera moves to reveal that the back door of the truck is beginning to lower. As it lowers, Valuska walks back towards it until he is directly in front of it.

As it lowers, we see within a dark void from which emerges the tale of the whale. Jangly circus music is being played on a speaker from somewhere within. An attendant sets up a little desk at the base of the truck’s ramp to sell tickets.

Valuska immediately walks forward and buys a ticket. The camera continues to follow him into the truck and the last shot we see of the outside world is the look of mingled fascination and fear on Valuska’s face as he first sees the whale up close.

Here, we get the first cut of the scene. approximately 4 minutes in. Tarr cuts from the above close-up of Valuska’ face to the scarred and mottled flesh of the whale. The cut occurs just as Valuska’s attention shifts from that of the outside world to focus entirely on the whale. Although the two scenes are completely continuous in time (and both shots on either side of the cut are 4 minute continuous long takes), they editing imposes a discontinuity to emphasize the otherworldliness of the whale and the immediacy of its presence.

For the next 4 minutes, Valuska walks soundlessly up and down the body of the whale. The whale itself takes up the entirety of the frame, dwarfing Valuska, such that we can never see more than a small slice of it at one time. The jangling, diegetic circus music of the previous scene is replaced by a haunting non-diegetic score. At one point we see a display of jars containing various preserved specimens, all alien and unidentifiable.

As Valuska leaves the truck, the camera stops following him and stays with the whale. Valuska, now shrouded in darkness, walks away, leaving us only with the carcass.

As Valuska leaves the truck, the camera stops following him and stays with the whale. Valuska, now shrouded in darkness, walks away, leaving us only with the carcass.

Out of focus in the distance, we see another man approach Valuska, and hear Valuska say to him, “How mysterious is the Lord that he amuses Himself with such strange creatures.” The shot lingers on the whale for almost 20 seconds after Valuska has left the frame.

The Hunters portrays people as pawns at the mercies of broad cultural and historical forces, with the corpse of the partisan’s appearance as the inciting event that reveals the fractures underlying the seeming cohesiveness of society.

Werckmeister Harmonies, however, takes the opposite approach. The corpse of the whale is presented as something so grand and incomprehensible that it can only be explained by invoking God. It is presented as wholly separate from that of the surrounding world, something profoundly beyond human understanding. Further, it is singularly presented from the perspective of a single POV character. This is not so much about the way historical forces act on individuals, but the way individuals perceive and try to comprehend those forces.

However, like the partisan, the appearance of the whale, too, reveals how tenuous the fibers holding society together are. While The Hunters explores the way violence integrates itself into the collective psyche of the culture, Werckmeister Harmonies explores the way violence manifests as an emergent property of this psyche.

An important aspect of the style of The Hunters is the way that it blends time and space, reality and fantasy, all within a single frame. For example, early in the movie, not long after finding the dead body and notifying the police (worth being extra explicit and clarifying that this action takes place in 1977), the hunters are seen lined up along a dock.

One of them turns around, and walks away alone. The camera follows him as he walks, taking off his hat and beginning to comb his hair.

After 30 seconds or so, he begins to pass people standing still and silent. We hear a voice being broadcast over speakers, talking about the US’s Marshall Plan helping Greece. The camera then leaves the hunter and pans further to the left, to reveal a giant projector screen. Behind the screen is a US Army tent, which the hunter approaches, re-emerging into the frame. The American commander, who it is revealed is the voice being broadcast, pauses to wordlessly hand instructions to the hunter.

As the hunter walks away, the Americans begin playing Casablanca on the projector.

This sequence is shot in a single continuous take 2:37 minutes long. However, it spans two different time periods, as the hunter walks from the dock in 1977 and arrives at a US Army camp in 1949, when the Americans were helping the Greek pro-capitalist forces purge the countryside of the communist partisans. That is, the discovery of the partisan body has caused the past to bleed seamlessly into the present. The movie continues to play with this idea, increasing in intensity to a point later in the film where the time period changes between two characters mid-conversation.

Finally, at the end of the movie, the fancy New Years ball the bourgeois hunters are throwing is interrupted when guerilla partisans impossibly appear before them right out of the past.

The dead body they discovered in the snow stands up and towers over them from the stage where they had hid him.

Without a word, the hunters and their wives gather up their jackets and head outside. The partisans lead them out to the dock where, earlier in the move, we see communists being executed by government forces as one of the hunters watches on approvingly.

The parties leave the house and walk past the camera, and we watch as the partisans line up and get their guns ready. As the once-dead body reads aloud from an official-sounding document, the camera pans slowly around so we can see the bourgeois lined up along the dock.

From off-screen, we hear “Fire!” And the hunters and their wives are dutifully shot dead.

The camera lingers on their bodies for 20 seconds. Suddenly, we cut back to the party, with all of the parties standing in the same positions they were in when the partisans arrived.

They stand around silently for thirty seconds before one opens the curtains on the stage to reveal the once-dead and now-dead again body. The parties gather around in contemplation.

As the camera zooms slowly in on the body (a process that takes approximately 1 minute), we begin to hear the same harsh wind sounds from the opening scene. From the body we cut back to the same winter landscape we saw when the hunters found the body in the first place.

From here, the closing scene is another long take, this time playing out as a reversal of the opening scene. The hunters emerge from the right-hand side of the screen, carrying the dead body. The place it back down in the same spot and rebury it in the snow. After a moment of silent contemplation they begin trudging back across the icy plain from which they had emerged. They get back into the same positions they had been standing in when the body was discovered. Once reset, they continue their originally interrupted hunting expedition as if nothing had happened.

The film ends with them disappearing back into the desolation, again becoming mere fixtures of the landscape.

When asked to confront a painful past that threatened their social order, the hunters chose not to confront it at all. They reburied the past and moved on as if nothing had happened in the first place. They don’t make any attempt to fix the fractures, they simply covered them with snow.

In contrast, the climax of Werckmeister Harmonies is a paroxysm of violence. As Valuska witnesses in silent horror, an emotionless throng ransacks the town. But there is no jubilation or revolutionary fervor. The violence is clinical and dutiful, as though everybody involved were doing it because they had to, not because they wanted to. As before, Tarr shoots it with excruciatingly long takes and slow, almost tender camera movements (there are 4 uninterrupted minutes of the crowd marching towards the camera; like with Valuska in the square, we only hear the sound of their feet marching in unison).

The violence peaks when the mob reaches the hospital. They beat patients in their beds and destroy furniture with the same solemn silence. It all comes to a stop when a couple of the rioters enter a bathroom to reveal a frail old man standing naked in a bathtub.

No words are exchanged. The rioters simply stop and walk slowly away from it all. Their expressions are just as blank as when they were rioting in the first place. The end to the violence is just as inscrutable as its beginning. Perhaps the violence stopped because such eviction of human frailty was humbling and forced them to realize the horror of what was going on; but, perhaps too, it was simply the business-like realization that they had already completed their purpose by destroying everything that was worth destroying (leaving only hollow husks behind).

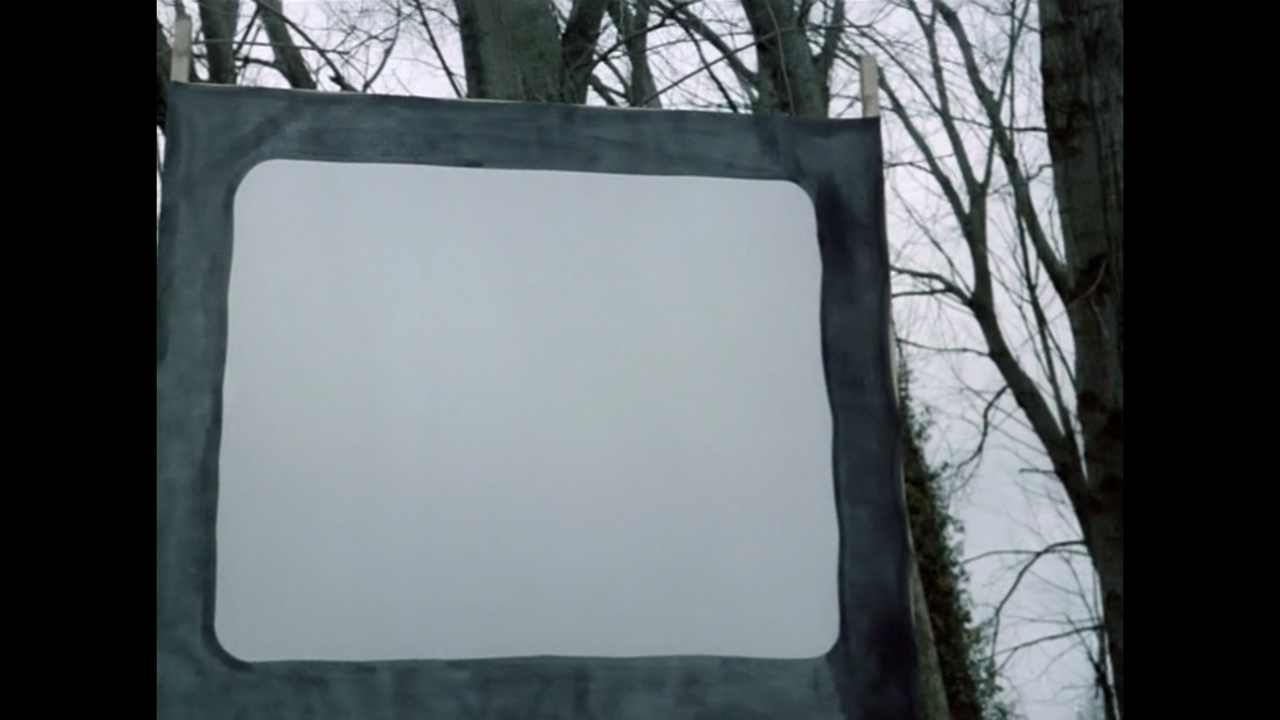

Not long after this scene, Valuska’s friend György Eszter goes to the town square to see the whale for the first time (after having visited Valuska who has committed himself to a mental institution due to his inability to cope with the horrors of the violence that he witnessed). For the first time, we see the whale from a wide angle so we can see it all at once, and not as fractured images.

The camera lingers on the whale, alone in an empty courtyard on the shattered remains of the truck, for over a minute, before Eszter enters the frame. The whale is no longer imposing, it is almost pitiful. It is a huge, rotting lump of flesh and nothing more. Eszter dwarfs it in the frame, emphasizing its smallness.

Mirroring Valuska’s experience of the whale, Eszter walks slowly up to its eye and gazes into it.

His expression is not one of wide-eyed wonder and fear like that of Valuska when the whale is first revealed. He regards the whale with sadness verging on bitterness. He walks away from the whale and the final shot of the movie is the whale becoming gradually concealed by the swirling mist.

The violence that engulfed the town was caused by nothing more than a rotten carcass. There is nothing about the whale that reveals any hard truths to confront like the body of the partisan did for the hunters. Nevertheless, simply the fact of its incomprehensible premise was sufficient for society to tear itself apart. And the perpetrators of the violence did not do so with any revolutionary zeal, or with any promise of a better future and bright tomorrow. The violence wasn’t premised on an attempt to right a perceived wrong or protect a way of life, it just was.

The Hunters makes explicit the historical context it is discussing and the way those events shaped the present, even while within a scene or frame Angelopoulos blends different time periods together. The future is superimposed on the present, as inescapable a facet of reality as our own physical presence.

Werckmeister Harmonies, on the other hand, makes no context explicit. The town Valuska lives in is never named. Neither is the country. The year is never enumerated. The entire movie exists in a nameless limbo. Yet even in its ambiguity it is intimate, almost painfully so, as it methodically follows the way historical forces impact the people least able to comprehend, never mind shape, those forces.

Many of the movies nominated for Best Picture this year are, in one way or another, also trying to reconcile our history with the present. Some of them may endure in our collective memories for years, others may disappear into as deep an obscurity as the films I just discussed. But I don’t think any of them will be as hauntingly strange, philosophically complex, or creatively idiosyncratic as either The Hunters or Werckmeister Harmonies. Very few movies are.