As I write this, Tropical Storm Florence (née Hurricane) is creeping westward across South Carolina. In a few hours, she will break up into a “tropical depression”, because wind speeds will drop below the apparently meaningful level of 39 mph. At which point she will creep up the spine of the Appalachian Mountains all the way up into New England, before drifting out to sea and dissolving somewhere over the North Atlantic. It will, I imagine, look a little like Jafar’s death in the direct-to-video Aladdin sequel, The Return of Jafar:

Currently, here in Durham, the sky is a flat grey and the wind is moving at school zone legal speeds. It isn’t raining, though it rained through most of the night. According to the Doppler radar, we are on the green fringes of the great orangish mass of ol’ Flo.

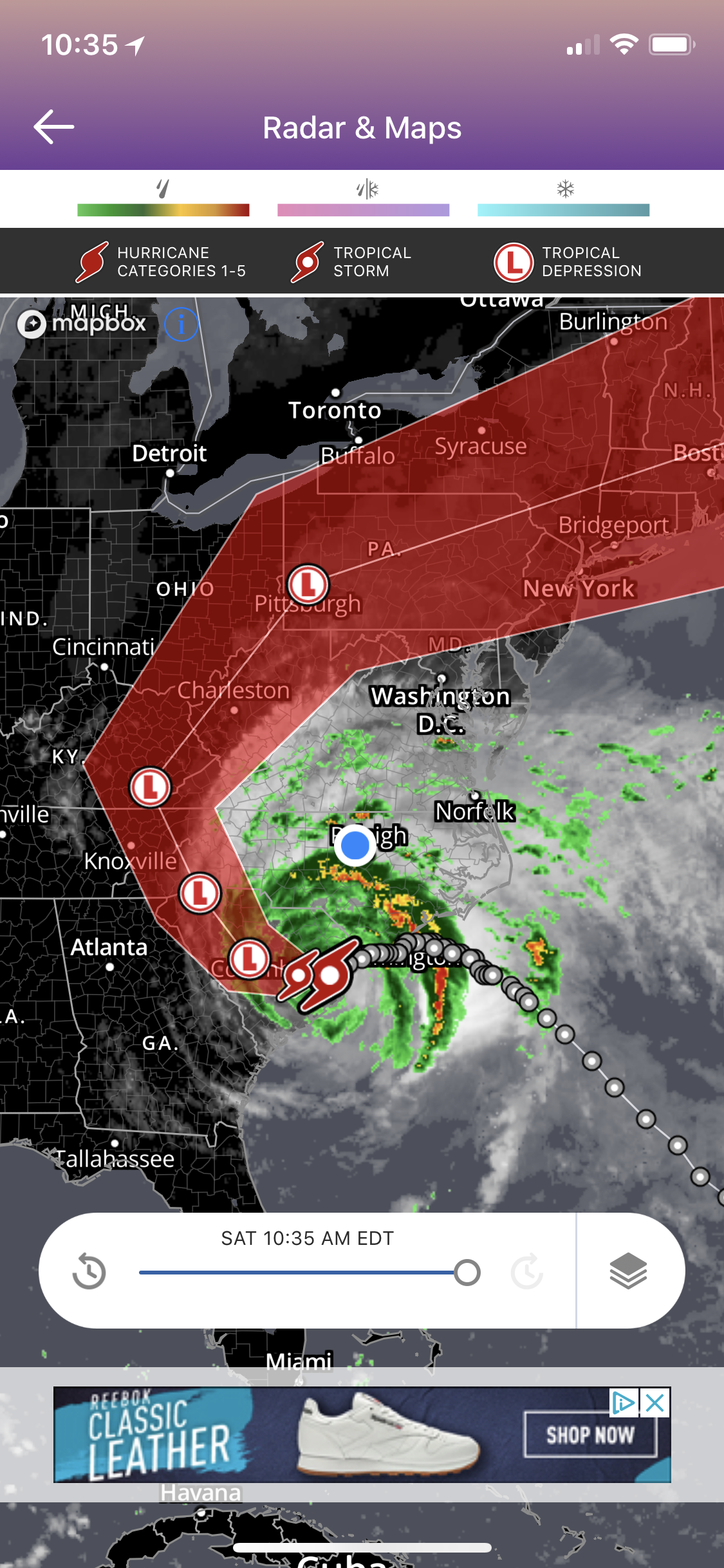

In fact, the Research Triangle area of NC has rather suspiciously been spared by the storm. I mean, look at this:

Sure, we can justify this in all sorts of ways as we talk about prevailing winds, atmospheric subsidence, and the Coriolis effect, but let’s face it, this looks like a pretty intentional decision to leave this area alone at the expense of just about every other part of the state. My best guess is that it is because the storm feels a kinship for the local NHL team (based in Raleigh – and shout-out to fellow blogcatter The Kid for giving me this joke).

There have been plenty of other “hot takes” about the storm’s path on social media. Even before the storm hit, there was a deluge of fake Facebook groups coming up with creative ways to curb the storm’s destruction (some of my favorites: “Bigfoot vs. Hurricane Florence”, “Everyone Point Fans at the Hurricane to Blow It Away”, and “Be too clingy to Flo so it leaves us”). And, of course, as with everything related to social media these days, these takes beget the backlash, as people point out that while some of us are safe and sound in Durham making jokes about how the storm wasn’t as intense as predicted, there are people who died and others who remain in legitimate peril in the parts of the state that weren’t as lucky. And that backlash begets the other backlash, as people justify the human impulse for humor in the face of tragedy, which begets yet more backlash, and so on and so forth, in a social media maelstrom as ferocious as the storm itself.

This isn’t unique to Florence. A similar pattern of activity came up during Hurricanes Irma and Harvey last year. But it still seems like a relatively new phenomenon; or, if not new, at least more prevalent and prominent that it had once been. I was in Wilmington, NC, two years ago, when Hurricane Matthew hit the coast, also as a Category 1; I don’t recall anything approaching the same level of scrutiny as Florence, and the reactions to Florence, have received. (Sidebar: going to the beach for a weekend during a hurricane is probably not the best idea. That said, the day after Matthew had passed was the perfect beach day: it was bright and sunny, with warm tropical waters, and the beaches were empty because nobody else was as stupid as we were).

It seems to reflect the general trend that social media has taken with regard to essentially every avenue of discourse: politics, sports, stand-up comedy, and so on. We already more or less have government-by-Twitter. We are well on our way to having justice-by-Twitter, too, as the cyclone of social media takes on high profile crimes tends to settle on a verdict long before the courts do (in most cases, the public spotlight is so far ahead that by the time the actual verdict is reached nobody cares enough to pay attention, or if they do it just reignites yet another storm debating the merits of that decision, etc.). Not that social media has created this, it is only channeling rather innate human qualities in a faster, more public, and more efficient way than previous media had allowed.

Not that this is an entirely negative thing, mind you. While social media has resulted in this clusterfuck of irreconcilable views and inculcated a stubborn refusal to listen or compromise, it has also made the job of emergency responders easier. It allows them to disseminate information to people in disaster areas quickly and easily, and grants people in those areas new avenues with which to reach out and get the help they need. As with anything, there are pros and cons. It’s not hard to spin it either way (any any spin results in a backlash, then a backlash, then …).

Hurricanes, though, compared to other natural disasters, tend to offer a rather unique reflection on this behavior and the feedback loops that precipitate it. Other natural disasters (and into this category I group any time Trump does anything) tend to be relatively unpredictable. They happen suddenly and without warning, so the social media loop more or less begins at the stage of dealing with the repercussions or fallout of the event. Hurricanes, though, we know about far in advance, typically at least a week. We can see in real time the storm rising up from warm equatorial waters like a genie out of a bottle and building strength as it barrels across the ocean.

They have just the right mixture of predictable and unpredictable to be compelling; we have a decent idea of what direction the storms will head in, allowing us to make estimates about their impact and danger, but they are prone to enough sudden changes in direction and speed that the forecasts are rarely completely correct. So this gives us several days of build-up, with constant updates and dire warnings that feed the social media storm the way the warmth of the oceans feed the real storm.

And, yes, on one hand it is good for news reports to focus on raising awareness of the danger the storm poses. Any hurricane, or tropical storm, is potentially dangerous, especially to coastal areas, and moreso to coastal areas that don’t have long histories of exposure to such events. On the other hand, the incessant barrage of apocalyptic scenarios and “STORM OF THE CENTURY” and “STRONGEST STORM TO EVER HIT THIS FAR NORTH” (Ron Howard voice: It wasn’t) has a tendency to numb people to the actual danger. It tends to provoke either panic or stubbornness, not carefully considered emergency preparation. The problem is that the incentives aren’t well aligned. The mainstream news media stands more to benefit from fearmongering, dramatic headlines, and click-bait, and the ensuing social media storm that follows, then it does from reporting and amending the basic facts as they evolve. If you pay attention the way the news carefully avoids mentioning that initial predictions were wrong or have changed, instead repeating the same doomsday scenarios with copy-and-pasted windspeed numbers, it’s all rather sickening, to be honest.

Do I have a solution? No, not really. Do I even have another clever hurricane joke to offer to balance out my lengthy diatribe on social media? No, all my hurricane jokes blow.

On a personal level, I just try to stay informed the best I can, while screening out the nonsense. It’s all about trying to find the right signal-to-noise ratio. But it’s not like I haven’t indulged in or contributed to this social media cyclone before, either. It’s hard to avoid the temptation, because it really is appealing to some of our pre-existing psychological impulses. Especially on a rainy day like today, it is hard to not just sit in front of the computer and see what everyone has to say and then offer my own opinions on top. Sometimes, though, I just need to remind myself to step away from the screen and look out the window.